With the arrival of the computer mouse came a very special game genre indeed.

The point-and-click adventure was birthed – a form that went on to do much to shape the conventions of the wider video game form. A historian of technology would rightly argue that the mouse had debuted as a working concept many years earlier, with Douglas Engelbart of the Stanford Research Institute putting together the first prototype 1964. It would be in the early-to-mid eighties, however, that computer mice started to appear as a standard of home computers – exactly the same time that the earliest purebred point-and-clicks began to emerge.

Around that time home computers were becoming more affordable, and ‘graphical user interfaces’ that used elements like icons, drop down menus and mouse control were beginning to secure the affections of the mainstream. And at the same time that more members of the public became familiar with the concept of controlling a cursor, the evolution of computing power was letting games communicate far more through the visual detail of their game worlds.

All of those things let point-and-click games emerge hot on the heels of early visual adventures – and they absolutely exist as a manifestation of a new wave of new technologies that converged in the home. Early examples of the form such as ICOM Simulations’ 1985 hardboiled detective drama Déjà Vu and Silicon Beach Software’s Enchanted Scepters took the groundwork laid by those that had adored text adventures with simple images (such as 1980’s Mystery House), and further developed the concept by harnessing the potential of the controllable cursor.

In case you’re still uncertain about what counts as a ‘point-and-click’, you aren’t alone. Simply put, there isn’t an absolute definition out there. They are, at a most fundamental level, ‘adventure games’ – that is, titles where interaction with and around the core narrative is the central focus. Many point-and-clicks ask you to solve a mystery or get to the bottom of the truth of a story, and they commonly place you in the shoes of a protagonist – or protagonists – that use conversation, observation and combining objects found scattered through the game world to solve puzzles and overcome plot-based barriers to progress.

It’s a genre that quite clearly owes a great deal to text adventures – and a key steppingstone in the evolution that led from those early written works to sweeping contemporary adventure forms such as open-world action-RPGs.

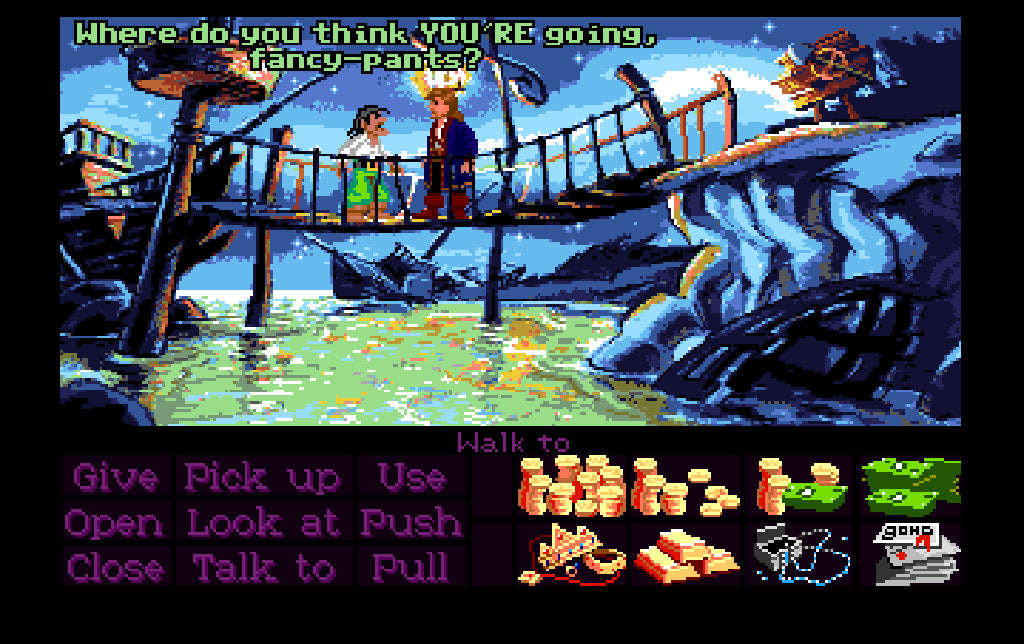

If names like Guybrush Threepwood, Gabrielle Knight, Roger Wilco or Sam and Max trigger any kind of nostalgic longing to spend time with a character that feels like an old friend, you’ve surely spent some time with a classic, iconic point-and-click.

And yet the genre’s earliest history is defined by a series that used keyboard control instead of a mouse. In late-1982 IBM had asked On-Line systems – later and better known as Sierra Online - to create a game for its forthcoming home computer, the PCjr. With IBM funding the development, King's Quest was born – and so too, many will tell you, so was the point-and-click adventure. It just didn’t involve pointing and clicking until remakes were realised. Rather, users would have to type the likes of ‘WALK LEFT’ into a text parser.

That speaks to the fact that some will tell you that the term ‘point-and-click’ overemphasises the control system’s role – and that really we are guilty of too eagerly subdividing up the broad ‘adventure game’ genre. And yet – while King's Quest’s original version certainly evokes much of the spirit of the point-and-click, it was arguably the mouse itself that unleashed the genre’s greatest potential – the feeling of being part of a world.

Compared to typing in text or prodding at arrow keys, using a mouse to point and click your way around a visual game world not only felt revolutionarily novel – it seemed personal and intimate, at least relative to other games of the time. To be able to check every detail of a game world with your new-fangled cursor – to poke around backgrounds and foregrounds alike and comb over almost every pixel – brought you closer to the game world. It made them feel present and living, and like you the player were the first visitor to really know those digital realms. Point-and-clicks also provided relative freedom to explore a world in your way, in the order you saw most fit, even if it meant taking the scenic route. They made gaming feel a little more like travelling, where you took the time to drink in the nuance of new places. They seemed to be more exploratory and… well… adventurous.

And yet the form was still limited in a way that so often lets creative game design thrive. So many point-and-click game makers of the golden era that spanned the eighties and nineties ‘only’ had the written world and simply animated visuals at their disposal – and in later years would stick to that template as the defining constraint of the genre. This emphasised the need for storytelling, character development and persona; indeed, they were the keystones that hold point-and-clicks together. For this reason, so many of the games needed to be well written, engrossing, and boiling with personality - because that was what they ultimately offered. That alone is a key reason the genre is commonly associated with humour. From Monkey Island to Sam and Max via Space Quest and Broken Sword so many point-and-clicks are known for their comedic knack. Jokes told through gameplay games captivated audiences while making game worlds feel more vibrant and alive.

Each of those titles also manages to spin a deeply engrossing story without all the mechanical bells and whistles of later, more intricate action-adventure releases. Perhaps, more than anything, point-and-clicks have such a flair for reeling you in because they are almost purely focussed on narrative – just as an arcade shmup presents one of the most direct examples of shooting gameplay. Releases like Day of the Tentacle draw close to all of your attention to narrative and character – those are what you interact with, explore and influence, almost entirely undistracted by other systems. And the immediacy and precision of the mouse counters any friction to you losing yourself to the narrative. Anyone who has struggled with zeroing in on the exact word to manually type within a text adventure will know what it feels like to be distanced from a story by ungainly systems of interaction.

The cursor, meanwhile, feels much more like an extension of the hand, giving you the sense of reaching right into islands riddled with piracy or steampunk-infused dystopian worlds.

All of that speaks to why point-and-clicks have had such an influential legacy, and endure to this day. Beyond the genre’s continuation in more recent examples such as the brilliantly witty Thimbleweed Park or the gorgeous Machinarium, so many games that employ storytelling to various degrees owe much to the genre.

Point-and-clicks didn’t invent the dialogue tree or inventory concept, but they did much to set the convention about how they would work in visual games. Déjà Vu and its genre-mates equally defined the rulebook around reining in the complexity of interactive stories, and let game developers build a grammar for environmental storytelling that players could understand. From their inception point-and-clicks also demonstrated that having narrative front-and-centre offered publishers a popular, bankable genre that had a natural tendency to produce sequels.

Yet for all this fawning over point-and-clicks, it’s worth remembering that they can be deeply frustrating experiences. It’s almost a trope of the genre that each title contains one puzzle of combining inventory items that feels in equal parts illogical and absurd. In the day’s before readily accessible game FAQs and video walkthroughs, long, frustrated evenings could pass as you tried to brute force a solution, randomly combining items while trying to interact with every bit of scenery imaginable. Without spoiling anything, if a mention of ‘the goat puzzle’ or ‘the monkey wrench’ sends a shudder down your spine, you know exactly what we are talking about.

Many point-and-clicks featured nonsensical puzzles, such as what to do with the aptly named 'Red Herring' in The Secret of Monkey Island

Even away from counterintuitive puzzles, point-and-clicks are prone to leaving the user clueless if they miss an important line of dialogue or a single interactive piece of the environment - something that turned out to be a lesson for many game designers who realised the value of not leaving a player without a sense of purpose or direction.

So point-and-clicks aren’t perfect? That hardly matters. Even talking a warts-and-all look at the genre reveals it to be something to be cherished – as a positive influencing force over the gaming medium at large, as a distinct genre that thrives thanks to the deliberate design constraints that define it, and as a comfortable place containing so many cosy, surreal and straight up hilarious adventures.

The mouse, it turns out, deserves a little more credit than we might give it.

For further reading, check out The Art of Point-and-Click Adventure Games – a stunning, 500-page coffee table book; a lovingly produced homage to the adventure games of yesteryear.